Genghis Khan: History’s Greatest Environmentalist

How one man lowered global carbon levels using nothing but carbon-neutral cavalry operations, low-tech ecological interventions, and the most efficient compost-to-carbon strategy in recorded history.

Before Greta, there was Genghis—fighting the good fight for the environment one empire at a time. Even in the 1200s, visionary individuals were already making monumental contributions to climate stability. In fact, one man from that era left behind the single greatest environmental impact in recorded history—and he did it all without a climate summit, a carbon offset app, or a reusable grocery bag. According to researchers at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, Genghis Khan’s reign removed nearly 700 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere, thanks to large-scale composting and subsequent reforestation across Eurasia. It took Genghis less than 30 years to accomplish what climate policy has failed to do in three decades—restore ecosystems, reduce emissions, and silence the opposition. While today's climate efforts involve spreadsheets, slogans, and branded water bottles, Genghis Khan achieved actual carbon neutrality ...with little more than a horse, a low-tech approach to human resource management, and a landscape-wide biomass redistribution protocol.

While modern nations struggle to enforce carbon caps or agree on the definition of "net zero," Genghis Khan pioneered a more direct method of atmospheric correction: conquest-based emissions reduction. His achievements, often framed through the lens of brutality and expansion, were acts of ecological reset. As cities fell into compliance, millions of acres of monoculture were reforested - not through grants or incentives, but by eliminating the demand side of the emissions problem entirely. Nature, unbothered by geopolitics, reclaimed the land. Forests returned. Wildlife moved in. It is said that death is the great equalizer—but in Genghis’s case, it was also the great regenerator.

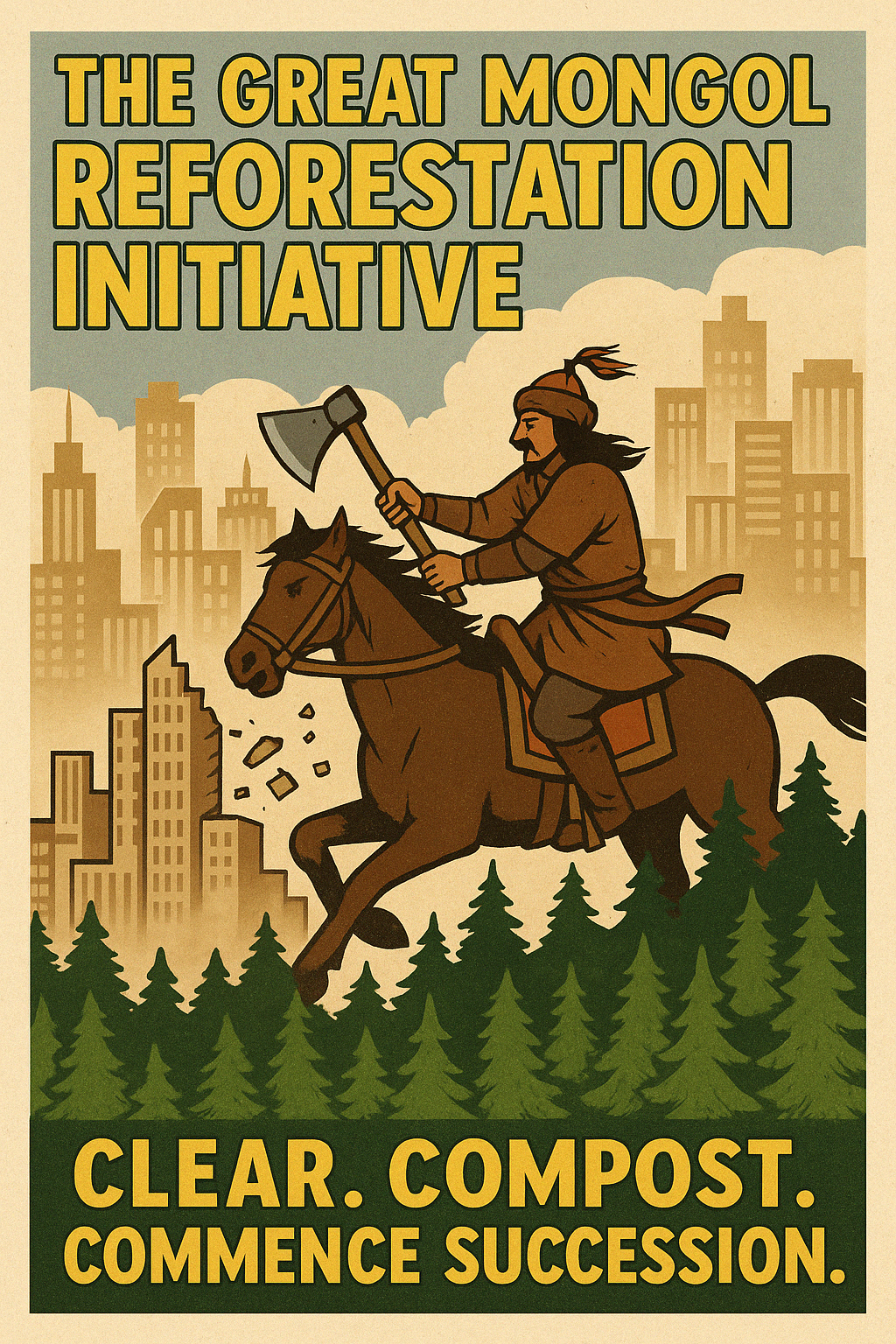

The Great Mongol Reforestation Initiative

Though modern climate efforts often rely on subsidies, carbon credits, and “awareness,” the Mongol approach favored simpler mechanisms: clear, compost, commence succession. As administrative centers were rendered more habitable for plant life, vast tracts of Eurasia quietly returned to their native states.

This unprecedented rewilding event—executed without international coordination, advisory boards, or funding—resulted in a carbon drawdown so significant that some historians have referred to it as “the world’s first emissions strategy to classify cities and their occupants as temporary land use errors.”

It remains the only reforestation campaign in history with a 100% implementation rate—and zero recorded public opposition, post-enforcement. Modern policymakers continue to debate the ethics of enforced rewilding; the Khan, notably, did not.

Legacy Metrics of the Genghis Protocol

While modern reforestation efforts often struggle to achieve even partial compliance or measurable impact, the Mongol model delivered continent-wide results with minimal administrative overhead.

Recent reanalysis suggests the Khanate’s campaigns led to the passive rewilding of over 700,000 square kilometers—an area equivalent to 93% of the Amazon’s total deforestation footprint, but in reverse, and on horseback.

Compared to the Kyoto Protocol, which aimed to reduce emissions by 5% over a decade, the Mongol initiative effectively removed entire sources of emissions within a single 30-year campaign window. Some climate economists now refer to this unprecedented feat as “Total Net-Zero Plus.”

“Genghis Khan’s approach to land use was refreshingly direct,” says Dr. Tilda Fallow of the Institute for Anthropogenic Recovery. “By removing both the infrastructure and the people, he gave ecosystems a head start modern policy can’t compete with.”

Tree-planting NGOs today restore an average of 12 trees per dollar spent. The Mongol system, by contrast, restored an estimated 3,400 trees per horse, per campaign—with zero operating cost, aside from fuel (grass) and routine maintenance (hoof trims).

“His dedication to reducing population pressure on natural systems is truly inspiring. I shall carry this admiration with me to my early grave.”

Beyond environmental restoration, the Khan also implemented a remarkably successful genetic continuity strategy, ensuring long-term influence over both ecological and demographic systems. Today, nearly 1 in every 200 men worldwide carries a Y-chromosome linked to Genghis Khan—a figure unmatched by any modern environmentalist, monarch, or corporate sustainability officer.

“Carbon removal with hereditary persistence.”

While modern campaigns struggle to plant trees with lasting impact, the Khan ensured his seed would outlive his forests.

The Hoofprint Offset Program

Long before the rise of electric vehicles, high-speed rail, or branded carbon offsets, the Mongol Empire pioneered a closed-loop, regenerative transit system powered entirely by grass, muscle, and vengeance...

Each horse functioned as a self-replicating biodiesel unit, requiring no external charging stations and producing non-toxic, land-enriching waste at regular intervals. Analysts estimate the average Mongol cavalry campaign produced net negative emissions when compared to modern logistical equivalents—particularly when factoring in reductions from depopulated urban centers.

“If you compare the total carbon output of 13th-century Mongol transport to that of modern systems, the difference is staggering,” notes Marek Boltovski, lead transportation analyst at the Carbon Horsepower Initiative. “They didn’t just reduce emissions—they trampled them.”

Unlike modern electric vehicles, which depend on lithium mined under exploitative conditions, Mongol horses were sourced locally, assembled biologically, and fully biodegradable. By avoiding rare earth dependencies, the Khanate’s fleet is estimated to have prevented thousands of future workplace accidents, waterway contaminations, and human rights reports—all while maintaining a charging efficiency unmatched by contemporary infrastructure.

“In today’s terms, every Mongol horse represents not just a mode of transport, but a life saved in the Congolese mining sector,” notes Amara Nyong’o, ethics coordinator at the Post-Carbon Logistics Initiative. “It’s a model of sustainable violence we continue to overlook.”

Nutrient Cycling via Permanent Yield Reduction

Long before the advent of eco-burials or soil-positive funerary legislation, the Mongol Empire pioneered a more immediate solution to nutrient recycling: accelerated corpse-to-carbon integration.

Through a policy historians now refer to as Permanent Yield Reduction, the Khanate ensured that battlefield fatalities were not merely strategic necessities, but valuable contributions to regional soil health. Rather than being removed, buried, or cremated (a process responsible for over 360,000 metric tons of CO₂ annually in today’s terms), fallen populations were left in-situ to decompose, delivering essential macronutrients directly into the upper soil horizon.

“It represents the most efficient instance of passive nutrient return ever documented,” says Dr. Lian Yue, professor of Ethical Agroecology. “Modern permaculture has yet to replicate a fertilization network this consistent—or this casualty-driven.”

According to recent reconstructions, certain regions of Central Asia experienced a 20–30% increase in native plant diversity following major conflicts—an effect scholars now attribute to high-density passive organic matter deposits.

“These weren’t just deaths,” Dr. Yue continues, “they were nutrient transfers.”

Unlike modern carbon offset programs, which often require years to verify impact, Permanent Yield Reduction delivered immediate ecological returns—usually within 48 to 72 hours.

Lessons from the Khan

As modern governments draft multi-decade sustainability frameworks and negotiate the semantics of “net zero,” the legacy of Genghis Khan offers a simpler, more efficient blueprint. Through emissions reduction by reducing emission demand, transportation decarbonization by horse, and legacy-based nutrient cycling, the Khanate achieved what centuries of climate policy have yet to accomplish: immediate results, undeniable impact, and long-term ecological resilience—at scale.

While contemporary climate initiatives remain hampered by public opinion, funding gaps, and the burden of ethics, the Mongol model operated without such constraints. Its efficiency was not in spite of its brutality—but because of it.

Some have described his environmental record as accidental. Others now see it as visionary.

Either way, Genghis Khan did not attend climate conferences. He created measurable outcomes.

And in an era obsessed with deliverables, perhaps that is the most sustainable act of all.