We Saved the Lake by Killing It!

Lake Huron is now so clear, scientists can see 80 feet down. Sounds like a success, right?

Wrong.

We didn’t heal the lake. We emptied it. Then we snapped a photo, posted it on Instagram, and called it restoration.

This is the kind of beauty you get when you Photoshop over a corpse.

Because when the water’s this clear… you can finally see the death you caused.

That crystal clarity? It’s collapse in disguise. The mussels ate the plankton. The plankton fed the fish. The fish fed the lake.

Now? It’s just silence.

And that silence?

That’s just crystal clear.

📍 Introduction: The Paradox of Preservation

They told us the lake was saved. The water? 💎Freaking Crystal! The reports? Phosphorescent! The grant money? 💸Spent.

But this isn’t a feel-good restoration story. It’s an ecological autopsy.

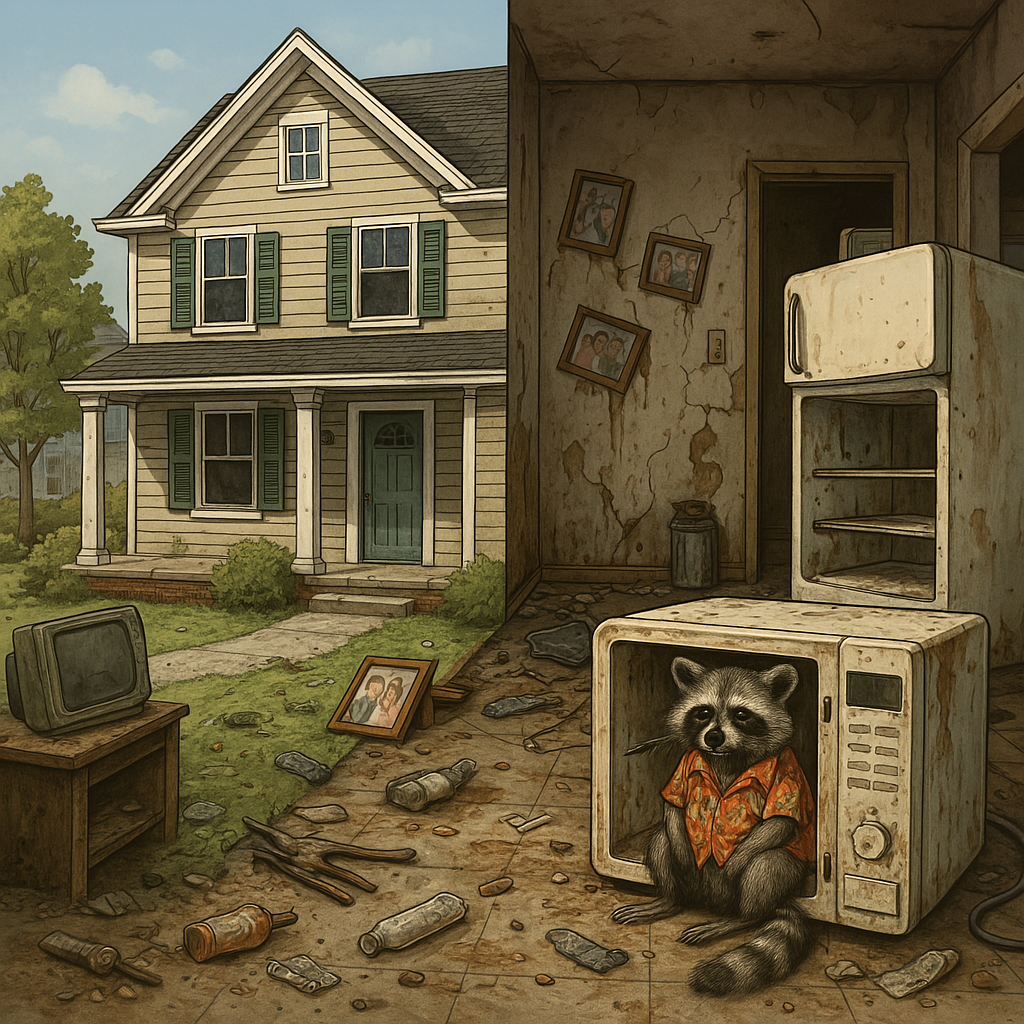

Imagine walking into a house that’s sparkling clean — the floors shine, the air smells like lemon, not a speck of dust in sight.

Then you find the family photos face down, the fridge unplugged, and a raccoon nesting in the microwave.

Welcome to modern “ecological restoration.”

We didn’t save nature — we ghosted it, cleaned up the scene, and called it a comeback.

When a lake is too clear, when the forest floor looks like a showroom, when the insects have vanished but the path looks freshly mulched…

That’s not progress. That’s Photoshop for ecosystems.

The problem isn’t that we don’t understand nature.

It’s that we keep trying to turn her into a brand.

🕳️ The Modest Origins of Lake Huron Syndrome

In the early days, Lake Huron was teeming with life — fish, plankton, and other unruly things that made the water look, frankly, unphotogenic.

So naturally, we intervened.

Through a brilliant series of invasive mussel introductions, industrial runoff, and strategic funding cutbacks, we succeeded in cleansing the lake of all that pesky biodiversity.

The plankton starved first — a necessary sacrifice, as they blocked the sunlight and made underwater photography a challenge.

Then the fish followed suit, removing the distracting movements and annoying “balance” of the food web.

At last, we were left with what every conservationist dreams of: a silent, transparent void.

We call this miracle Lake Huron Syndrome™ — a model of clarity, minimalism, and ecological austerity.

Some might say we destroyed the lake.

But to them we say: show us a prettier corpse.

🌊 1. The Illusion of Clarity: Microplastics in Lake Huron

“Clean water doesn't mean clean ecosystems.”

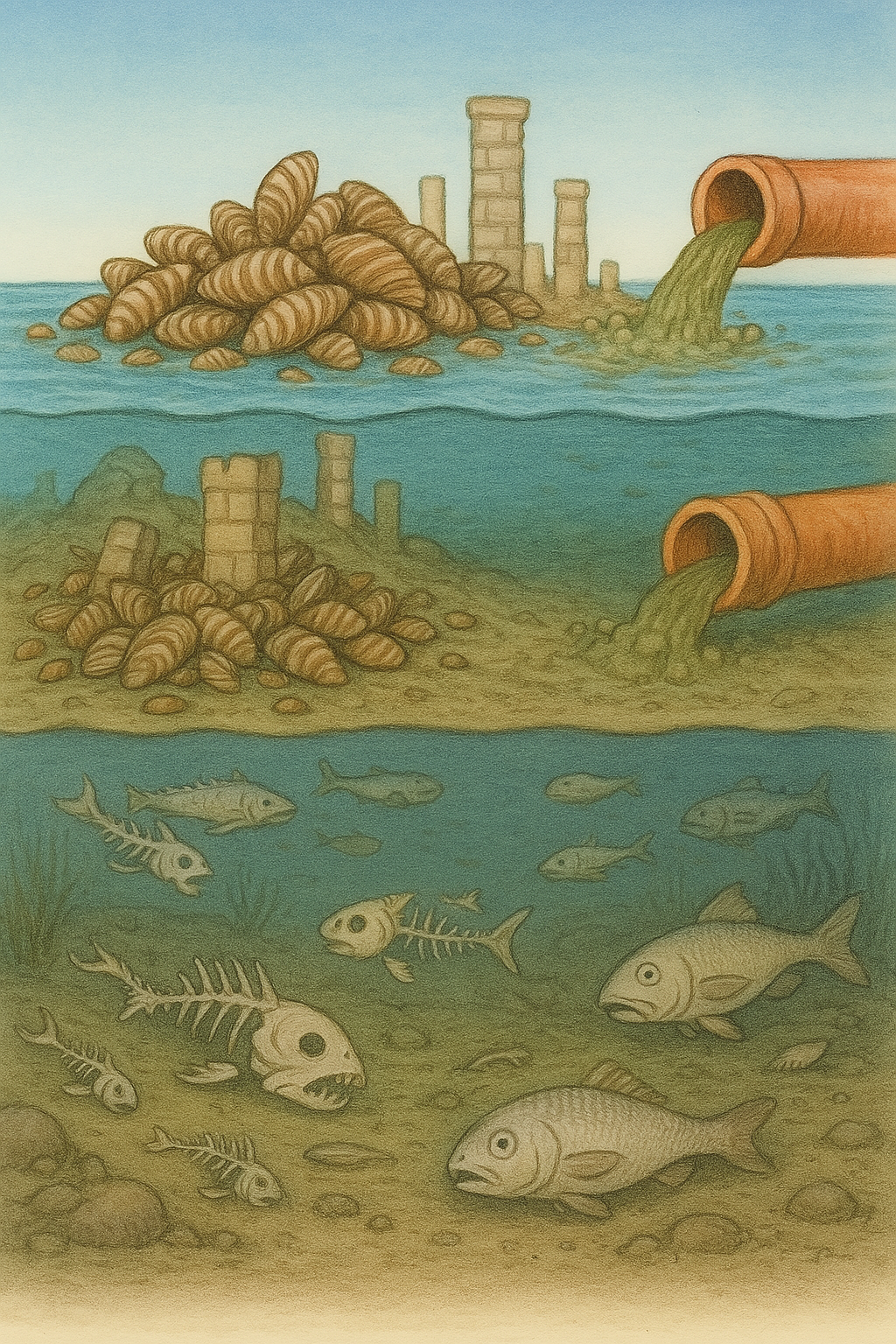

Microplastics plague the lake, according to scientific reports. Invasive zebra mussels filter the water — and in doing so, filter out life. Clarity here is a death mask, not a badge of health.

Studies by the International Joint Commission and the University of Toronto found that over 80% of surface water samples in Lake Huron contain microplastics, including microfibers from synthetic clothing and microbeads from personal care products.

Invasive mussels filter out plankton and suspended nutrients, clearing the water—yes—but in doing so, they remove life-sustaining particles. The water becomes optically clean but ecologically sterile.

⚡️ 2. Chemical Contaminants: The Unseen Threat

Legacy pollutants still haunt the lake. PFAS (forever chemicals) are now being found in fish, mussels, and sediment — some so new they don’t even have names.

According to the 2022-2026 Lakewide Action and Management Plan (LAMP), the lake still receives pollutants such as mercury, PCBs, and dioxins from legacy industrial discharge. Moreover, PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), also known as “forever chemicals,” have been found in fish tissue and drinking water sources.

In 2021, researchers at Environment and Climate Change Canada found over nine previously unrecorded PFAS compounds in Great Lakes sediments and aquatic species—chemicals that persist for decades without breaking down.

🌿 3. Invasive Species: Unintended Consequences

Zebra mussels. Quagga mussels. Round gobies.

They weren’t supposed to define the lake. Now they do. These invaders turned the food web upside down — and we called it "restoration." It’s like starving an ecosystem and admiring how skinny it got.

Quagga and zebra mussels, originating from Eurasia and introduced through ballast water, now dominate the benthic zone of Lake Huron. These mussels filter an astonishing one liter of water per day per mussel, removing beneficial phytoplankton while leaving behind pollutants they cannot process.

This disrupts energy flow and nutrient cycling, particularly phosphorus, leading to a cascade failure in the ecosystem. The Round Goby, another invasive species, thrives on mussels but outcompetes native fish.

🌫️ 4. The Deceptive Surface: A Metaphor for Everything

Lake Huron Syndrome is our world’s reflection: sterile, aesthetic, hollow. Corporations greenwash. Governments delay enforcement. People think silence means healing.

We confuse stillness with peace. But that stillness? It's grief.

Lake Huron Syndrome represents how society often values aesthetics over substance:

- Corporate environmentalism that prioritizes optics over impact

- Policy changes that are unfunded or unenforced

- Communities lulled into complacency by clear water and clean reports

Real restoration requires long-term thinking, not visual cleanup. Healing starts at the bottom, both ecologically and psychologically.

🌺 Conclusion: Clarity Is Not Redemption

The lake isn’t fine. It’s quiet because it has nothing left to say.

If we want to restore real systems, we need to start from the bottom — the rot, the muck, the microbial networks that don’t photograph well.

“We saved the lake by killing it!”

What we call “restoration” today too often amounts to greenwashing—simplified narratives for complex ecological trauma.

Laugh. Then get to work.